Chapter 2:

Electricity Transition in 2022

In this chapter

Electricity is at its cleanest as wind and solar hit 12%

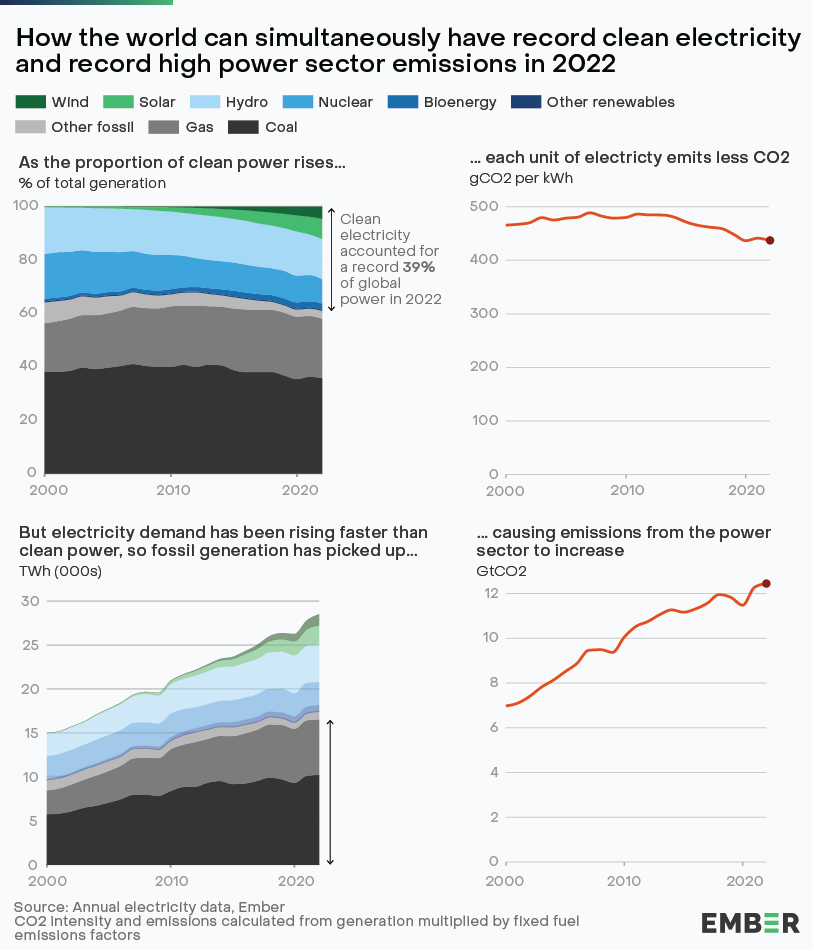

2022 beat 2020 as the cleanest ever year, as emissions intensity reached a record low of 436 gCO2/kWh. Wind and solar reached a record 12% of global electricity generation, but they still weren’t built fast enough to meet all of the world’s increasing need for electricity. Consequently, coal and other fossils met the remaining gap, driving up emissions to a new record high.

Wind and solar help reduce emissions intensity of electricity

Record growth in wind and solar pushed electricity to its cleanest level ever: 436 gCO2/kWh.

Solar added a record 245 TWh of generation in 2022, while wind added a record 312 TWh. As a result, 12% of the world’s electricity came from solar and wind. That’s up from a tenth of global electricity generation in 2021, which in itself was up from just 5% when the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015. Combined, solar and wind overtook nuclear generation in 2021 and are catching up with hydro generation. Over sixty countries now generate more than 10% of their electricity from wind and solar.

The first fall in other clean electricity since Fukushima

In 2022, clean electricity sources–excluding solar and wind–saw their first year-on-year fall in generation since the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011. This was primarily because nuclear generation fell by 129 TWh (-5%) as France’s nuclear fleet suffered major outages and Germany and Belgium closed some reactors. In addition, growth in global hydropower was held back in regions that experienced extreme droughts, notably in the EU where generation fell by 66 TWh to its lowest level since at least 1990.

Demand increased

Global electricity demand grew by 2.5% (+694 TWh) in 2022, similar to the average growth of 2.6% in the previous decade (2010-2021). Much of last year’s increase was driven by demand increases in major economies, and three of them alone accounted for 93% of the global demand growth: China (54%), the US (21%), and India (18%). In contrast, electricity demand fell by 3% in the EU due to a combination of mild weather and efforts to reduce consumption in the face of affordability pressures and security of supply concerns (see chapter 6 for details).

Wind and solar met the majority of demand growth

In 2022 growth in wind and solar met 80% of the increase in electricity demand, while all renewables together met 92% of the rise. In China, wind and solar met 69% of the growth in electricity demand in 2022, while all clean sources met 77%. In India, wind and solar met 23% of the demand growth, while all clean sources provided 38%. In the US, wind and solar met 68% of the demand growth.

Coal increased to meet the shortfall

Coal and other fossil fuels (mainly oil) increased to meet the remainder of the rise in electricity demand, as well shortfalls from nuclear and gas generation. Coal rose by 108 TWh (+1.1%) year on year, reaching a record high generation of 10,186 TWh. Other fossil generation rose by 86 TWh (+11%).

Trends among countries and regions varied significantly: coal fell in the US (-70 TWh, -7.8%) in 2022 compared to the year before, but rose in China (+81 TWh, +1.5%), India (+92 TWh, +7.2%), Japan (+9.7 TWh, +3.1%), and in the EU (+27 TWh, +6.4%).

Coal power’s increase of 1.1% is in line with average growth in the last decade. One might have expected a larger rise in coal generation in 2022, given the price spikes in gas and security of supply concerns. But at a global level, there was actually as much switching from coal to gas, as there was switching from gas into coal. That is in part because gas prices were already higher than coal before 2022, so much of the switching into coal had already happened the year before. It is also in part because of the US, where three major factors–coal plant retirements, coal transport disruption and new gas power plant capacity–led to a substantial switch from coal to gas generation, as gas prices stayed much lower than in the rest of the world.

Gas plateaued

Global gas generation declined slightly by 0.2% (-12 TWh) in 2022 compared to the previous year. It might have been expected that high, volatile gas prices would cause a bigger fall in gas, however the energy crisis did not lead to large-scale gas-to-coal switching (as described above).

However, at a national level, some countries still saw increases in gas generation. For example, gas generation rose in the US (+7.3%), where it is replacing coal. But gas generation fell in most other countries, including Brazil (-46%) and Türkiye (-32%) due to good hydro generation, and in India (-22%) due to high gas prices.

Other fossil fuels–mainly oil– increased by 86 TWh, where there were some instances of gas-to-oil switching (although this datapoint is a little tentative, because of poor reporting by Middle Eastern countries which have the majority of oil generation).

Emissions reached a record high

Overall, fossil generation rose by 183 TWh (+1.1%) in 2022, setting a new record. As a result, power sector CO2 emissions rose by 160 million tonnes (+1.3%) reaching a record high of 12,431 mtCO2. Emissions intensity is heading in the right direction, but absolute emissions are not yet falling. This means that the power sector is not yet seeing the emissions cuts needed for net zero, as emissions should be falling by an average 7.6% annually this decade, as per the IEA Net Zero Emissions scenario.

2022 was an accelerator year for the transition to renewables

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the global energy crisis in 2022 may well be remembered as a turning point that made many governments rethink their reliance on fossil fuels. Energy security concerns and new policies led to the largest ever upward revision of IEA’s renewable power forecast in 2022.

The EU’s REPowerEU plan was developed to rapidly reduce reliance on fossil fuel imports from Russia, largely by growing the use of renewable electricity and improving energy efficiency. In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act that was introduced in August 2022, directs nearly $370 billion of government funding to clean energy, with the goal of substantially lowering the nation’s carbon emissions by the end of this decade. Other major economies continued to roll-out existing policies, like China’s 14th Five-Year Plan and new market reforms.

Additionally, investment in clean energy technologies matched that of fossil fuels for the first time in 2022. Developing economies like Indonesia and Viet Nam secured commitments for international funding in 2022 from historic high emitters like the UK, US, and EU to support them in displacing coal with renewables and hence decoupling their economic growth from emissions.

The energy crisis provides a clear motive for low-carbon energy transitions: the need for greater energy diversification, reduced reliance on fossil fuels, and an acceleration of renewable energy. However, the crisis also risks locking in some fossil infrastructure, with some countries securing long term contracts for gas.

While 2022 may be seen as the turning point, the impacts of the policy developments on clean electricity agreed throughout the year won’t be felt for a while. The change that we have witnessed so far in clean power and in electrification is therefore only the tip of the iceberg.

Related Content